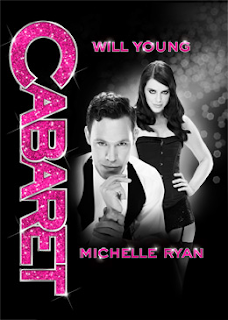

Will Young’s Emcee is like a wind-up Weimar man-doll, coin-operated,sneering and smirking, plucking at his crotch like a small boy whose just awoken to the new toy between his legs. He’s got the voice for it and he is a strong central presence but he begins shrill and continues upwards; there’s little shade, little sorrow, little sense of things to come.

He’s certainly game, white-faced and wide-eyed, idly stroking his inner thigh or stomping across the stage like a bulbous Mr Creosote during The Money Song, and there are times when this combination of plastic malevolence and high camp are put to good use, particularly during Tomorrow Belongs to Me where he sits atop the set like a sinister Von Trapp child puppeting the dancers below.

When he’s allowed to be still, to downplay – drifting across the stage in a plum coloured robe during the melancholy I Don’t Care Much or appearing as a ghostly watchful background presence – it’s actually very effective. But these moments are few and far between. At least his showman’s gloss and constant facial contortions compensate somewhat for the sucking absence elsewhere in production. The emotional entanglement between Sally Bowles, star attraction at the Kit Kat Club, and Clifford Bradshaw, the sexually questing American would-novelist and Isherwood stand-in, never feels real. There’s little sense of connection between them, sexual or otherwise. This is mainly down to the casting of Bionic ex-Eastender Michelle Ryan as Sally; her voice is both polished and powerful, but lacking in character which seems the inverse of what it should be. (And here it’s hard not to draw a comparison with Rebecca Humphries’ bubbly, vulnerable take on the role in the recent Southwark Playhouse production of I am a Camera – a Sally who while maddening would definitely be someone fun to share a gin or three with). Ryan’s Sally is kind of joyless and kind of lifeless too, a little too clean and pink – while her fingernails may be green, I bet it’s a manicure job – and though Matt Rawle’s Clifford is warmer, he has little to play against.

It’s the tentative and ultimately doomed relationship between Sian Philips’ ageing Fraulein Schneider and Linal Haft’s Herr Schultz that gives the production’s its initial emotional charge and the moment when he blithely decides to stay in Berlin, despite the yellow star of David daubed on his shop window, because he believes all “this will pass” is genuinely upsetting.

It’s left to Javier de Frutos’ choreography to give the production the raw edges that are not evident elsewhere. The dancers’ movements are angular and sometimes ugly, resounding with the slap of skin on skin. Black clad bodies tumble and plunge from a wheeled metal platform during Sally’s opening number and Clifford is given a stylised Clockwork Orange-style kicking by Nazi street thugs. Norris steers the production from the decadent whirl of the early scenes towards something altogether more nightmarish and chilling and the last tableau – as the stage is bathed in shadows, the West End glitter drops away and the dancers cower and huddle, exposed in every sense – is incredibly stark and chilling, one that still has the power to appal, to make the audience gasp and shudder and still their hands.

Reviewed for Exeunt

No comments:

Post a Comment